Neural Variational Monte Carlo

Published 2024-11-17

One interesting application area of AI in the sciences is quantum chemistry. At the center of quantum chemistry lies the Schrödinger equation. This equation can be solved ab initio, meaning purely from first principles without any experimental data or external knowledge. Accurate solutions to the Schrödinger equation are essential for determining the electronic structure of molecules or materials, which in turn can be used to derive physical and chemical properties. Therefore, the ability to quickly produce accurate solutions to the Schrödinger equation is of upmost importance in fields such as materials discovery, drug development and more. In this blog post, I will introduce the Schrödinger equation, a method for solving it called variational Monte Carlo, and how neural networks can be used to obtain accurate solutions. Throughout, we will be using JAX to implement the method.

The Schrödinger equation

The time-independent Schrödinger equation can be written as

\[\hat{H}\psi(\mathbf{X}) = E\psi(\mathbf{X})\]which is an eigenvalue problem for the electronic Hamiltonian $\hat{H}$. This is an operator that describes the energy of the electrons, which we will elaborate on further below. The wavefunction $\psi$ is the eigenfunction, and the $E$ is the eigenvalue that is the energy of the system. The wavefunction is a function of $\mathbf{X} = \left(\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, …, \mathbf{x}_N \right)$ which are the states of each of the $N$ electrons in a system. Each $\mathbf{x}_i$ consists of a position $\mathbf{r}_i\in\mathbb{R}^3$ and spin $\mathbf{\sigma}_i \in \{\uparrow, \downarrow\}$. We are interested in finding the ground state energy $E_0$, or lowest energy solution to the equation, along with the associated wavefunction, $\psi_0$.

The Variational Principle

The variational principle states that for any trial wavefunction $\tilde{\psi}$,

\[E_v = \frac{\braket{\tilde{\psi}|\hat{H}|\tilde{\psi}}}{\braket{\tilde{\psi}|\tilde{\psi}}} \geq E_0\]Where the equality $E_v = E_0$ holds if and only if the trial wavefunction is the equal to the ground state wavefunction, $\tilde{\psi} = \psi_0$. A great introduction to the quantum chemistry which covers this is (Szabo & Ostlund, 1996, p. 32). This principle provides us with a useful optimization strategy: any modification to our trial wavefunction that lowers its variational energy $E_v$ brings us closer to the true ground state energy $E_0$. This gives us a clear objective function to minimize when searching for the ground state wavefunction. While there are several ways of doing this, we will look into one called variational Monte Carlo.

Variational Monte Carlo

Let us consider a trial wavefunction $\psi_\theta$, with some parameters $\theta$. Using the variational principle above, we can create a loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$ that we seek to minimize:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \frac{\braket{\psi_\theta|\hat{H}|\psi_\theta}}{\braket{\psi_\theta|\psi_\theta}} = \frac{\int \psi_\theta^*(\mathbf{X})\hat{H}\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int \psi_\theta^*(\mathbf{X}) \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X}) \,d\mathbf{X}}\]This can be rewritten in terms of $|\psi_\theta|^2$, which is proportional to the probability of the electron distribution.

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \frac{\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \frac{\hat{H}\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}}\]Through Monte Carlo sampling of $X$ from the density $|\psi_\theta|^2$ we can write this loss as an expectation over configurations:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2} \left[ \frac{\hat{H}\psi(\mathbf{X})}{\psi(\mathbf{X})} \right]\]The term we are taking the expectation of is referred to as the “local energy”, $E_\text{local}$:

\[E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) = \frac{\hat{H}\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}\]Substituting this term into the loss equation, we can now write it simply as:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2} \left[ E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\right]\]Now that we have defined our loss function, we can start to implement the code. Before we can implement $E_\text{local}$, however, we must define our Hamiltonian operator $\hat{H}$. While there are many options, we are interested in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which assumes the nuclei of the system are fixed in space and is often used for variational Monte Carlo calculations. This can be written as:

\[\hat{H} = -\frac{1}{2}\sum_i \nabla^2_i + \sum_{i>j} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{r}_j|} - \sum_{iI} \frac{Z_I}{|\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{R}_I|} + \sum_{I>J} \frac{Z_I Z_J}{|\mathbf{R}_I - \mathbf{R}_J|}\]where $\nabla^2$ is the Laplacian with respect to electron $i$, $\mathbf{r}_i$ and $\mathbf{R}_I$ are positions of electron $i$ and atom $I$ respectively, and $Z_I$ is the charge of atom $I$.

Typically, this is written as a sum of the kinetic energy (the first term) and the potential energy (the remaining three terms). With this Hamiltonian operator defined, we can start writing our python code, starting with a function to compute the local energy of some positions:

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

import numpy as np

def local_energy(wavefunction, atoms, charges, pos):

return kinetic_energy(wavefunction, pos) + potential_energy(atoms, charges, pos)

def kinetic_energy(wavefunction, pos):

"""Kinetic energy term of Hamiltonian"""

laplacian = jnp.trace(jax.hessian(wavefunction)(pos))

return -0.5 * laplacian / wavefunction(pos)

def potential_energy(atoms, charges, pos):

"""Potential energy term of Hamiltonian"""

pos = pos.reshape(-1, 3)

r_ea = jnp.linalg.norm(pos[:, None, :] - atoms[None, :, :], axis=-1)

i, j = jnp.triu_indices(pos.shape[0], k=1)

r_ee = jnp.linalg.norm(pos[i] - pos[j], axis=-1)

i, j = jnp.triu_indices(atoms.shape[0], k=1)

r_aa = jnp.linalg.norm(atoms[i] - atoms[j], axis=-1)

z_aa = charges[i] * charges[j]

v_ee = jnp.sum(1 / r_ee)

v_ea = -jnp.sum(charges / r_ea)

v_aa = jnp.sum(z_aa / r_aa)

return v_ee + v_ea + v_aa

To verify our energy calculation, we can compute the expectation of the energy of a system with a Hydrogen atom at the origin, and one electron, which has an exact ground state wavefunction proportional to ${\psi(\mathbf{r})=\exp(-|\mathbf{r}|)}$:

def wavefunction_h(pos):

return jnp.exp(-jnp.linalg.norm(pos))

atoms = np.array([[0.0, 0.0, 0.0]])

charges = np.array([1.0])

pos = np.random.randn(3) # randomly sample electron position

print(local_energy(wavefunction_h, atoms, charges, pos))

0.5

This matches the ground state energy of a hydrogen atom, which is -0.5 Hartree.

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

Now that we have coded up the local energy, let us revisit our loss function. We have figured out $E_\text{local}$, but how do we sample $\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2$? While we can compute the probability density $\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2$ easily with our wavefunction, it is not easy to directly sample points from this distribution for any $\psi_\theta$. In order to obtain random samples from the distribution we will use a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method known as Metropolis-Hastings. Samples are generated sequentially by generating a proposal configuration from the previous sample, and then randomly accepting or rejecting that proposal with a likelihood dependent on the value of the probability distribution at the proposed configuration point.

More specifically, starting with some initial configuration $\mathbf{X}$, one Metropolis algorithm step can be written as:

- Generate a proposal $\mathbf{X}^\prime$ from some prior distribution $Q(\mathbf{X^\prime}|\mathbf{X})$. In our case $Q(\mathbf{X^\prime}|\mathbf{X})$ will be a normal distribution centered at the positions of $\mathbf{X}$.

- Compute acceptance ratio $A = \frac{|\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X}^\prime)|^2}{|\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2}$.

- Generate random number $u \in [0, 1]$.

- Accept the proposal, setting $\mathbf{X}= \mathbf{X}^\prime$ if $u \leq A$, otherwise $\mathbf{X}$ remains at the same value.

Intuitively, proposals that are more equal or more likely than the current configuration will always be selected, and lower likelihood proposals will only get selected proportionally to how low their likelihood under the target distribution is. Over many steps, this leads to a distribution of configurations properly represents the target distribution $\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2$. We can write a function to perform many Metropolis-Hastings steps below:

import equinox as eqx

from functools import partial

from collections.abc import Callable

@eqx.filter_jit

@partial(jax.vmap, in_axes=(None, 0, None, None, 0))

def metropolis(

wavefunction: Callable,

pos: jax.Array,

step_size: float,

mcmc_steps: int,

key: jax.Array,

):

"""MCMC step

Args:

wavefunction: neural wavefunction

pos: [3N] current electron positions flattened

step_size: std of proposal for metropolis sampling

mcmc_steps: number of steps to perform

key: random key

"""

def step(_, carry):

pos, prob, num_accepts, key = carry

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

pos_proposal = pos + step_size * jax.random.normal(subkey, shape=pos.shape)

prob_proposal = wavefunction(pos_proposal) ** 2

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

accept = jax.random.uniform(subkey) < prob_proposal / prob

prob = jnp.where(accept, prob_proposal, prob)

pos = jnp.where(accept, pos_proposal, pos)

num_accepts = num_accepts + jnp.sum(accept)

return pos, prob, num_accepts, key

prob = wavefunction(pos) ** 2

carry = (pos, prob, 0, key)

pos, prob, num_accepts, key = jax.lax.fori_loop(0, mcmc_steps, step, carry)

return pos, num_accepts / mcmc_steps

With the Metroplis-Hastings step written, we can test it on our hydrogen wavefunction. Below we visualize a histogram of several electron configurations though each Metropolis-Hastings step. While the distribution has a poor initialization, it eventually aligns well with the exact radial density function of the ground state wavefunction for hydrogen, which is $4r^2e^{-2r}$.

Neural Wavefunctions

Optimization

With our sampling procedure $\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2$ defined, we are almost ready to train our neural wavefunction. Like most deep learning methods, we will train the wavefunction parameters $\theta$ through gradient descent. To do this we must obtain gradients of these parameters with respect to the loss, $\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L(\theta)}$. We cannot simply take the expectation of the gradient of the local energy across our samples, $\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2} \left[\nabla_\theta E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\right]$, as the samples are dependent $\theta$, and will therefore bias the gradient. Luckily, we can compute an unbiased estimate of the gradient, written as:

\[\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\theta) = 2\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X}) \left(E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) - \mathcal{L}(\theta) \right) \right]\]which we derive in the Appendix. Following (Spencer et al., 2020) we can write a function that correctly computes our loss and gradient of loss as a function with custom Jacobian-Vector product:

def make_loss(atoms, charges):

# Based on implementation in https://github.com/google-deepmind/ferminet/

@eqx.filter_custom_jvp

def total_energy(wavefunction, pos):

"""Define L()"""

batch_local_energy = jax.vmap(local_energy, (None, None, None, 0))

e_l = batch_local_energy(wavefunction, atoms, charges, pos)

loss = jnp.mean(e_l)

return loss, e_l

@total_energy.def_jvp

def total_energy_jvp(primals, tangents):

"""Define the gradient of L()"""

wavefunction, pos = primals

log_wavefunction = lambda psi, pos: jnp.log(psi(pos))

batch_wavefunction = jax.vmap(log_wavefunction, (None, 0))

psi_primal, psi_tangent = eqx.filter_jvp(batch_wavefunction, primals, tangents)

loss, local_energy = total_energy(wavefunction, pos)

primals_out = loss, local_energy

batch_size = jnp.shape(local_energy)[0]

tangents_out = (jnp.dot(psi_tangent, local_energy - loss) / batch_size, local_energy)

return primals_out, tangents_out

return total_energy

Building a Neural Network

We are now ready to construct our wavefunction neural network. This function will take our input $\mathbf{X} = \left(\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, …, \mathbf{x}_N \right)$ and produce a single value, equal to the evaluation of the wavefunction at the given electron configuration. While this sounds straightforward, there are a few considerations that need to be made. First, our wavefunction must be antisymmetric under the exchange of the coordinate $\mathbf{x}$ of two electrons, meaning:

\[\psi_\theta(\mathbf{x}_1, ..., \mathbf{x}_i, ..., \mathbf{x}_j, ..., \mathbf{x}_N) = -\psi_\theta(\mathbf{x}_1, ..., \mathbf{x}_j, ..., \mathbf{x}_i, ..., \mathbf{x}_N)\]This is necessary to achieve the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that two identical particles cannot occupy the same quantum state, i.e. the wavefunction must evaluate to zero if $\mathbf{x}_i =\mathbf{x}_j$. This is typically done by formulating our wavefunction as a sum of determinants, where each determinant consists of $N$ neural network functions $\phi(\cdot)$ evaluated on each of the $N$ electrons:

\[\psi(\mathbf{x}_1, ..., \mathbf{x}_N) = \sum_k \begin{vmatrix} \phi_1^k(\mathbf{x}_1) & ... & \phi_1^k(\mathbf{x}_N) \\ \vdots & & \vdots \\ \phi_N^k(\mathbf{x}_1) & ... & \phi_N^k(\mathbf{x}_N) \\ \end{vmatrix} = \sum_k\det[\Phi_k]\]Determinants are useful for achieving this antisymmetry as they have a desirable property that it changes sign if two rows or columns or swapped, meaning our wavefunction will change sign if two electrons are swapped.

Another property we want our wavefunction to have is a finite integral. Since $|\psi_\theta|^2$ is proportional to a probability distribution, it must be finite in order for the normalized integral to be equal to $1$. This can be achieved by enforcing $\lim_{\mathbf{r}\rightarrow\infty}\psi_\theta(\mathbf{r}) = 0$, which is also desirable as it reflects the idea that an electron has a low probability from being found far outside an atom. This can be achieved by representing our functions $\phi(\cdot)$ as a Slater orbital:

\[\phi^k_i(\mathbf{x}_j) = h^k_i(\mathbf{x}_j) \sum_m \pi^k_{im} \exp({\sigma^k_{im}|\mathbf{r}_j - \mathbf{R}_m|})\]where $\pi$ and $\sigma$ are learned coefficients for each determinant $k$, orbital $i$, and atom $m$, and $h(\cdot)$ is a neural network. In models like FermiNet (Pfau et al., 2020), $h(\cdot)$ is implemented as a simple permutation equivariant architecture with mixing across electron features. In Psiformer (von Glehn et al., 2023), this is replaced with a transformer architecture. For simplicity, we will assume we only have one atom at the origin, and use a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) that is applied independently to each electron given three features: the displacement vector from the atom $\mathbf{r}_j$, the scalar distance from the atom $|\mathbf{r}_j|$, and an encoding of the spin ($1$ for spin-up and $-1$ for spin-down).

class Linear(eqx.Module):

"""Linear layer"""

weights: jax.Array

bias: jax.Array

def __init__(self, in_size, out_size, key):

lim = math.sqrt(1 / (in_size + out_size))

self.weights = jax.random.uniform(key, (in_size, out_size), minval=-lim, maxval=lim)

self.bias = jnp.zeros(out_size)

def __call__(self, x):

return jnp.dot(x, self.weights) + self.bias

class PsiMLP(eqx.Module):

"""Simple MLP-based model using Slater determinant"""

spins: tuple[int, int]

linears: list[Linear]

orbitals: Linear

sigma: jax.Array

pi: jax.Array

def __init__(

self,

hidden_sizes: list[int],

spins: tuple[int, int],

determinants: int,

key: jax.Array,

):

num_atoms = 1 # assume one atom

sizes = [5] + hidden_sizes # 5 input features

key, *keys = jax.random.split(key, len(sizes))

self.linears = []

for i in range(len(sizes) - 1):

self.linears.append(Linear(sizes[i], sizes[i + 1], keys[i]))

self.orbitals = Linear(sizes[-1], sum(spins) * determinants, key)

self.sigma = jnp.ones((num_atoms, sum(spins) * determinants))

self.pi = jnp.ones((num_atoms, sum(spins) * determinants))

self.spins = spins

def __call__(self, pos):

# atom electron displacement [electron, atom, 3]

ae = pos.reshape(-1, 1, 3)

# atom electron distance [electron, atom, 1]

r_ae = jnp.linalg.norm(ae, axis=2, keepdims=True)

# feature for spins; 1 for up, -1 for down [atom, 1]

spins = jnp.concatenate([jnp.ones(self.spins[0]), jnp.ones(self.spins[1]) * -1])

# combine into features

h = jnp.concatenate([ae, r_ae], axis=2)

h = h.reshape([h.shape[0], -1])

h = jnp.concatenate([h, spins[:, None]], axis=1)

# multi-layer perceptron with tanh activations

for linear in self.linears:

h = jnp.tanh(linear(h))

phi = self.orbitals(h) * jnp.sum(self.pi * jnp.exp(-self.sigma * r_ae), axis=1)

# [electron, electron * determinants] -> [determinants, electron, electron]

phi = phi.reshape(phi.shape[0], -1, phi.shape[0]).transpose(1, 0, 2)

det = jnp.linalg.det(phi)

return jnp.sum(det)

First we define a simple Linear layer to use in our network. Our neural

network PsiMLP is then initialized with a list of these linear layers, along

with parameters pi and sigma for the Slater orbitals. The forward pass,

defined in __call__() simply computes the features, passes them through the

MLP, and constructs the orbitals phi. These orbitals are reshaped into square

matrices, and their determinants are computed to obtain the final wavefunction

value. For the MLP we use $\tanh(\cdot)$ as a nonlinearity, as the wavefunction

must be continuous at all points, and nonlinearities such as ReLU introduce

discontinuity points.

Training

With our Metroplis sampling, loss function, and neural network defined, we can now train the neural network to minimize the variational energy. Training is performed in several steps:

- Initialize electron positions at some random Gaussian distribution (like the hydrogen animation above).

- Perform MCMC for several warmup steps in order to obtain a better initial distribution.

- Keep repeated training steps consisting of MCMC steps updating the positions of $\mathbf{X}$ and gradient optimization of the model weights $\theta$ using $\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{X})$.

Overtime, the model will update the wavefunction to approch the true ground state wavefunction, while updating the electron positions through MCMC to accurately reflect the distribution of the updated wavefunction.

import optax

from tqdm import tqdm

def vmc(

wavefunction: Callable,

atoms: jax.Array,

charges: jax.Array,

spins: tuple[int, int],

*,

batch_size: int = 4096,

mcmc_steps: int = 50,

warmup_steps: int = 200,

init_width: float = 0.4,

step_size: float = 0.2,

learning_rate: float = 3e-3,

iterations: int = 2_000,

key: jax.Array,

):

"""Perform variational Monte Carlo

Args:

wavefunction: neural wavefunction

atoms: [M, 3] atomic positions

charges: [M] atomic charges

spins: number spin-up, spin-down electrons

batch_size: number of electron configurations to sample

mcmc_steps: number of mcmc steps to perform between neural network

updates (lessens autocorrelation)

warmup_steps: number of mcmc steps to perform before starting training

step_size: std of proposal for metropolis sampling

learning_rate: learning rate

iterations: number of neural network updates

key: random key

"""

total_energy = make_loss(atoms, charges)

# initialize electron positions and perform warmup mcmc steps

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

pos = init_width * jax.random.normal(subkey, shape=(batch_size, sum(spins) * 3))

key, *subkeys = jax.random.split(key, batch_size + 1)

pos, _ = metropolis(wavefunction, pos, step_size, warmup_steps, jnp.array(subkeys))

# Adam optimizer with gradient clipping

optimizer = optax.chain(optax.clip_by_global_norm(1.0), optax.adam(learning_rate))

opt_state = optimizer.init(eqx.filter(wavefunction, eqx.is_array))

@eqx.filter_jit

def train_step(wavefunction, pos, key, opt_state):

key, *subkeys = jax.random.split(key, batch_size + 1)

pos, accept = metropolis(wavefunction, pos, step_size, mcmc_steps, jnp.array(subkeys))

(loss, _), grads = eqx.filter_value_and_grad(total_energy, has_aux=True)(wavefunction, pos)

updates, opt_state = optimizer.update(grads, opt_state, wavefunction)

wavefunction = eqx.apply_updates(wavefunction, updates)

return wavefunction, pos, key, opt_state, loss, accept

losses, pmoves = [], []

pbar = tqdm(range(iterations))

for _ in pbar:

wavefunction, pos, key, opt_state, loss, pmove = train_step(wavefunction, pos, key, opt_state)

pmove = pmove.mean()

losses.append(loss)

pmoves.append(pmove)

pbar.set_description(f"Energy: {loss:.4f}, P(move): {pmove:.2f}")

return losses, pmoves

For optimization, we use the Adam optimizer and clip the norm of the gradient at

1.0 for stability during training. Hyperparameters such has mcmc_steps,

warmup_steps, step_size, and learning_rate have been adjusted in order to

converge quickly on example case we are about to demonstrate.

Example: Lithium Atom

For a simple demonstration of our code, let us train our PsiMLP model to find

the ground state energy of the lithium atom. We can model this as a single atom

at the origin with a charge of ${Z=3}$, and 3 electrons:

# Lithium at origin

atoms = jnp.zeros((1, 3))

charges = jnp.array([3.0])

spins = (2, 1) # 2 spin-up, 1 spin-down electrons

We can then instantiate our neural wavefunction, and optimize using the vmc()

training function we wrote above:

key = jax.random.key(0)

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

model = PsiMLP(hidden_sizes=[64, 64, 64], determinants=4, spins=spins, key=key)

losses, _ = vmc(model, atoms, charges, spins, key=subkey)

losses will contain the estimate total energy over each step in training run.

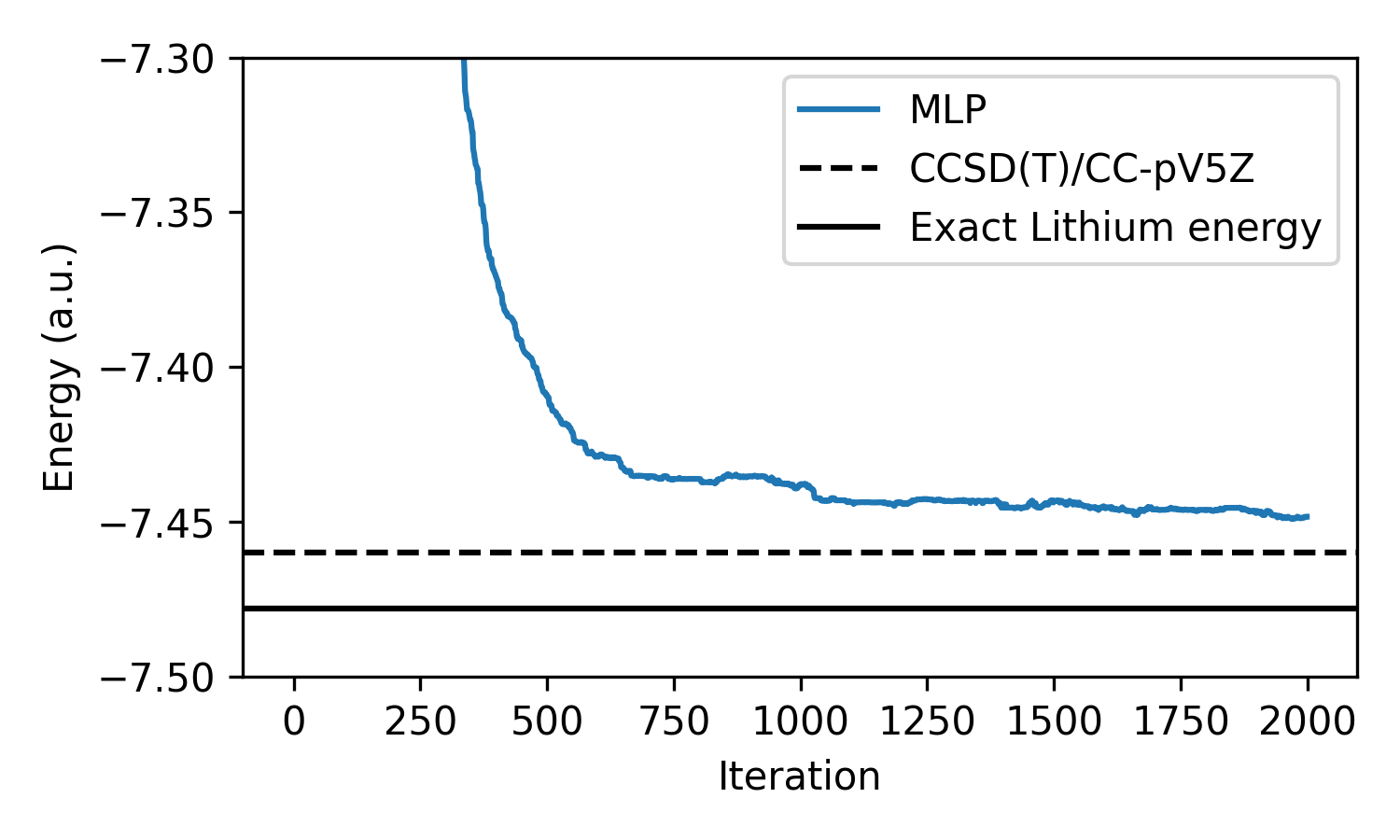

Since this estimate is often still noisy (despite many Monte Carlo samples), it

is typical to smooth these estimates overtime to visualize the progression of

the model. We can compare the progression of our neural wavefunction energies to

energies calculated with coupled

cluster (CCSD(T)), a highly accurate

quantum chemistry method, and the exact ground state energy which has been

derived analytically.

def smooth(losses, window_pct=10):

# smooth losses with median of last 10% of samples

window = int(len(losses) * window_pct / 100)

return [np.median(losses[max(0, i-window):i+1]) for i in range(len(losses))]

# Smoothed loss from model

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4), dpi=300)

plt.plot(smooth(losses), label="MLP")

# CCSD(T) calculation

import pyscf

import pyscf.cc

basis = "CC-pV5Z"

m = pyscf.gto.mole.M(atom="Li 0 0 0", basis=basis, spin=1)

mf = pyscf.scf.RHF(m).run()

mycc = pyscf.cc.CCSD(mf).run()

et_correction = mycc.ccsd_t()

e_tot = mycc.e_tot + et_correction

plt.axhline(e_tot, c="k", ls="--", label=f"CCSD(T)/{basis}", zorder=3)

# Exact from https://journals.aps.org/pra/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevA.47.3649

plt.axhline(-7.47806032, c="k", label="Exact Lithium energy", zorder=3)

plt.legend()

plt.ylim(-7.5, -7.3)

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.ylabel("Energy (a.u.)")

We can see that the MLP-based wavefunction converges nicely; however, it does

not reach the energy of the CCSD(T) calculation or analytical solution. This

means our neural network is still far from modeling the exact ground-state

wavefunction. In order to do this we will need to make the model more

expressive, particularly with respect to electron-electron interactions. Since

the MLP operates on each electron independently, our PsiMLP model has no way

of modelling these interactions, which we know effect the energy from looking at

the Hamiltonian.

Electron-electron Interactions

One simple and effective way of introducing electron-electron interaction to our model is by adding a Jastrow factor. This can be done by simply adding a term $e^{\mathcal{J}(\mathbf{X})}$ to our wavefunction:

\[\psi(\mathbf{X}) = e^{\mathcal{J}(\mathbf{X})}\sum_k\det[\Phi_k]\]There are many options for ways to parameterize this factor. One simple function that obeys the electron-electron cusp conditions (Foulkes et al., 2001) is the Padé-Jastrow function:

\[\mathcal{J}(\mathbf{X}) = \sum_{i<j} \frac{\alpha |\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{r}_j|}{1 + \beta |\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{r}_j|}\]where $\alpha = \frac{1}{4}$ for same-spin electron pairs, i.e. $\sigma_i =

\sigma_j$, and $\alpha = \frac{1}{2}$ for opposite-spin electron pairs, i.e.

$\sigma_i\neq\sigma_j$. The other parameter $\beta$ is a single additional

parameter that we will optimize along with the rest of the neural network

weights. We can implement this by extending our PsiMLP model with an

additional beta parameter and computation of the Padé-Jastrow factor defined

above.

class PsiMLPJastrow(PsiMLP):

beta: jax.Array # parameter for Jastrow

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.beta = jnp.array(1.0)

def __call__(self, pos):

det = super().__call__(pos) # get determinant from PsiMLP model

pos = pos.reshape(-1, 3)

i, j = jnp.triu_indices(pos.shape[0], k=1)

r_ee = jnp.linalg.norm(pos[i] - pos[j], axis=1)

alpha = jnp.where((i < self.spins[0]) == (j < self.spins[0]), 0.25, 0.5)

jastrow = jnp.exp(jnp.sum(alpha * r_ee / (1.0 + self.beta * r_ee)))

return det * jastrow

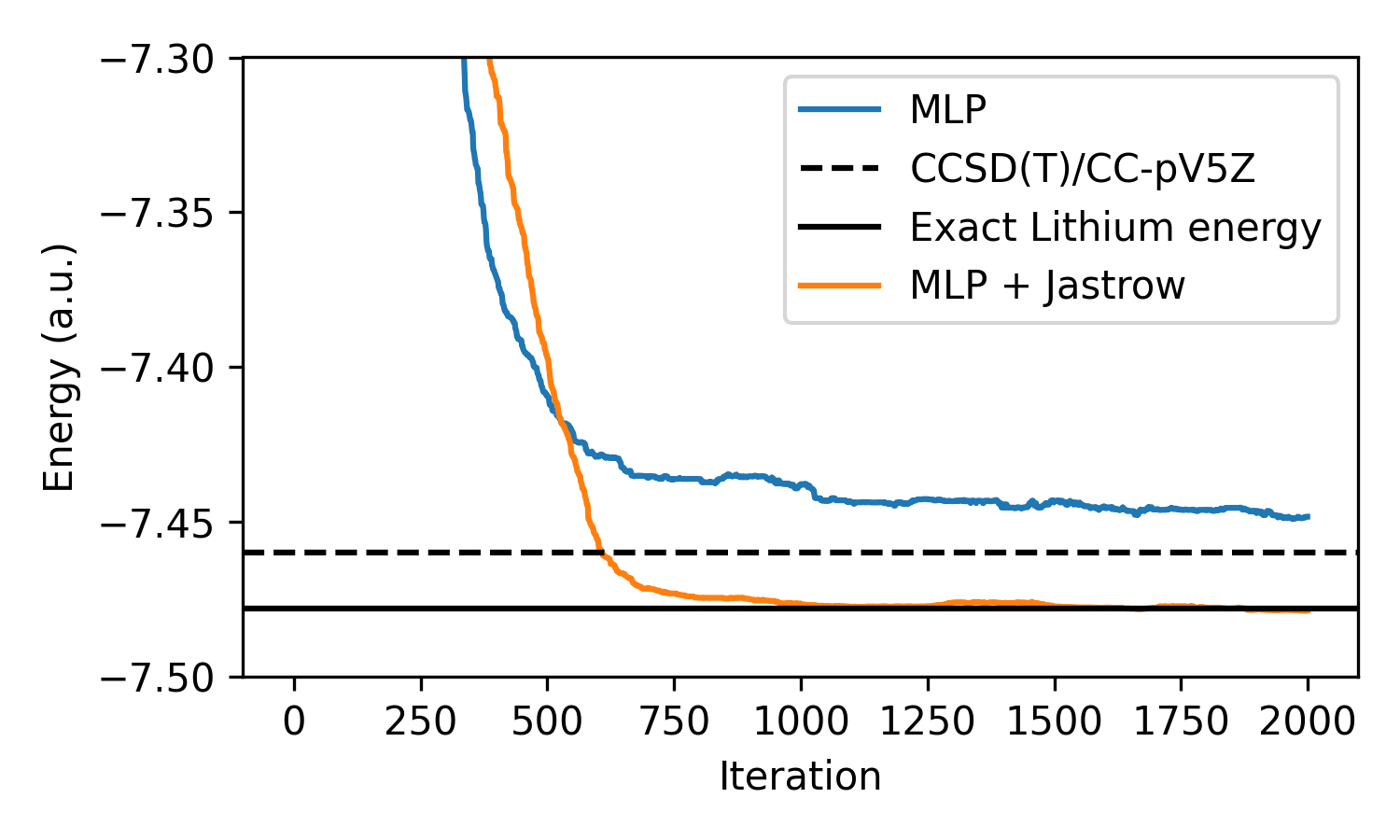

With our new PsiMLPJastrow network defined we can now train it one our lithium

atom configuration as before:

model = PsiMLPJastrow(hidden_sizes=[64, 64, 64], determinants=4, spins=spins, key=key)

losses, _ = vmc(model, atoms, charges, spins, key=subkey)

plt.plot(smooth(losses), label="MLP + Jastrow")

We can see that the addition of this Jastrow function with only a single additional parameter allows the neural network to achieve lower energy than the CCSD(T) calculation, but converges to the exact ground state energy of the lithium atom!

While the model we use in this post is quite simple, it is a great demonstration on how neural VMC can be used to calculate quantum mechanical properties with greater accuracy than more traditional methods such as couple cluster. Furthermore, we show how the addition of physics-informed priors, such as the Jastrow factor, can greatly improve model performance with negligible overhead. In practice, there are several further modifications that can be made to improve the accuracy of neural VMC methods:

- Computing the determinant in log space, such as with jnp.slogdet which is less likely to have numerical issues than the determinant itself.

- Using more expressive architectures instead of MLPs, such as Transformer layers (von Glehn et al., 2023).

- Using second-order optimization methods such as K-FAC (Martens & Grosse, 2015)

The full code for this post can be found at github.com/teddykoker/vmc-jax.

Appendix

Derivation of unbiased estimate of $\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\theta)$. First recall definition of $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \frac{\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} \end{aligned}\]Take gradient:

\[\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \nabla_\theta \frac{\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}}\]Simplify, noting wavefunction is real-valued, so $\nabla_\theta |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 = 2\frac{\nabla_\theta \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})} |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2$.

\[\begin{aligned} \nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\theta) &= \frac{\nabla_\theta \int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} - \frac{\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X})\,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} \frac{ \nabla_\theta \int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}}\\ &= \frac{\int 2 \frac{\nabla_\theta \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})} |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) \,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} - \frac{ \mathcal{L}(\theta) \int 2 \frac{\nabla_\theta \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})} |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}}\\ &= \frac{\int 2\frac{\nabla_\theta \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}{\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})}\left(E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) - \mathcal{L}(\theta) \right) |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}}\\ &= \frac{\int 2 \nabla_\theta \log \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X}) \left(E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) - \mathcal{L}(\theta) \right) |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} {\int |\psi_\theta(\mathbf{X})|^2 \,d\mathbf{X}} \end{aligned}\]Write as expectation over Monte Carlo sampling of $X$ from the density $|\psi_\theta|^2$:

\[\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}(\theta) = 2\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}\sim|\psi_\theta|^2} \left[\nabla_\theta \log \psi_\theta(\mathbf{X}) \left(E_\text{local}(\mathbf{X}) - \mathcal{L}(\theta) \right) \right]\]- Szabo, A., & Ostlund, N. S. (1996). Modern quantum chemistry: introduction to advanced electronic structure theory. Courier Corporation.

- Spencer, J. S., Pfau, D., Botev, A., & Foulkes, W. M. C. (2020). Better, Faster Fermionic Neural Networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.07125

- Pfau, D., Spencer, J. S., de G. Matthews, A. G., & Foulkes, W. M. C. (2020). Ab-Initio Solution of the Many-Electron Schrödinger Equation with Deep Neural Networks. Phys. Rev. Research, 2(3), 033429. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.033429

- von Glehn, I., Spencer, J. S., & Pfau, D. (2023). A Self-Attention Ansatz for Ab-initio Quantum Chemistry. In ICLR.

- Foulkes, W. M. C., Mitas, L., Needs, R. J., & Rajagopal, G. (2001). Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of solids. Reviews of Modern Physics, 73(1), 33.

- Martens, J., & Grosse, R. (2015). Optimizing neural networks with kronecker-factored approximate curvature. International Conference on Machine Learning, 2408–2417.